Physical activity

You may find that exercise can cause low blood glucose (hypoglycaemia), or occasionally high blood glucose (hyperglycaemia). It is important that you become familiar with how different types of activity affect your blood glucose levels.

To understand the impact of exercise on blood glucose, there are a few key principles:

- Knowing how much insulin you have ‘on board’ when you are exercising.

You need some insulin in your body whilst exercising to push the glucose from the blood into the muscles. If you have very little or no insulin in your body, the glucose in your blood will rise during exercise, and your muscles won’t get the energy they need.

More commonly, you will have sufficient insulin on board, but have not eaten enough carbohydrate to counter the increase energy demand, and there is a risk of the blood glucose going low.

We’ve created some scenarios below to help you manage some common problems that people with type 1 can experience when exercising.

Paul has type 1 diabetes and recently joined a gym that offers morning exercise classes. He manages his diabetes with long-acting insulin (Lantus) once daily before bed and takes fast-acting insulin (Actrapid) with meals. The classes last 30 minutes and he usually attends either a morning high-intensity interval training class (HIIT) class or a morning yoga class. Paul finds that despite having an in-range blood glucose level when starting the HIIT class, his blood glucose is usually high after the class is finished. He doesn’t ever have this problem when he attends yoga class.

Paul has type 1 diabetes and recently joined a gym that offers morning exercise classes. He manages his diabetes with long-acting insulin (Lantus) once daily before bed and takes fast-acting insulin (Actrapid) with meals. The classes last 30 minutes and he usually attends either a morning high-intensity interval training class (HIIT) class or a morning yoga class. Paul finds that despite having an in-range blood glucose level when starting the HIIT class, his blood glucose is usually high after the class is finished. He doesn’t ever have this problem when he attends yoga class.

Paul speaks to his diabetes care team who help him understand what is going on. They explain that in most people with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose responses to physical activity can be highly variable depending on the type or timing of physical activity. As a result, it’s important to check blood glucose before, regularly throughout, and after physical activity to understand how types of exercise can affect you. Usually, adjusted carbohydrate intake or insulin doses are needed to keep blood glucose in range.

Blood glucose spiking after high intensity (anaerobic exercise) is very common and occurs due to the body releasing stress hormones (e.g., adrenaline) which cause the liver to release glucose into the blood. Because of this, Paul sees his blood glucose rise with high-intensity exercise (HIIT) but not with lower-intensity exercise (yoga). Generally, people can try to target this by doing a lower-intensity (anaerobic) cooldown (such as walking or cycling) which will bring blood glucose levels down. Alternatively, they could discuss with their diabetes team if a small correction dose may be appropriate in these situations.

Cathy likes to go running on weekdays during her lunch break after she has eaten. She has type 1 diabetes and manages this with a basal-bolus insulin regime including rapid-acting insulin with meals (Fiasp) or for correction doses and long-acting insulin (Lantus) before bed. Cathy monitors her blood glucose using a FreeStyle Libre.

Cathy likes to go running on weekdays during her lunch break after she has eaten. She has type 1 diabetes and manages this with a basal-bolus insulin regime including rapid-acting insulin with meals (Fiasp) or for correction doses and long-acting insulin (Lantus) before bed. Cathy monitors her blood glucose using a FreeStyle Libre.

Cathy carb counts and injects 6 units of Fiasp to cover her lunch. Her blood glucose when she set out on her run was 6.2 mmol/L. She notices her blood glucose starts to drop and after around 20 minutes her blood glucose has dropped to 3.9 mmol/L. Cathy decides to stop running and treats her hypoglycaemia with two glucose tablets. Cathy doesn’t usually have problems with hypos during her runs when she runs in the afternoon on her days off work, but often stops her lunchtime runs due to hypos.

- Using a temporary basal rate reduction on his insulin pump for 6–8 hours after he plays football to prevent hypoglycaemia. This temporary basal rate reduction duration could be longer if Rohan noticed he was experiencing hypos later overnight.

- Having a snack before bed, ideally a low glycaemic index food.

Rohan has type 1 diabetes and uses an insulin pump (Omnipod DASH) and a FreeStyle Libre 2 flash glucose monitor. Rohan likes to play football in the evenings from 7–8pm and managed to keep his blood glucose mostly in range during exercise with a combination of snacks or correction bolus doses when he thinks they are required. Rohan finds than on days he plays football in the evening he has hypoglycaemia overnight and is woken up by his FreeStyle Libre 2 alarm at around 2am when his blood glucose drops below 4 mmol/L.

Rohan has type 1 diabetes and uses an insulin pump (Omnipod DASH) and a FreeStyle Libre 2 flash glucose monitor. Rohan likes to play football in the evenings from 7–8pm and managed to keep his blood glucose mostly in range during exercise with a combination of snacks or correction bolus doses when he thinks they are required. Rohan finds than on days he plays football in the evening he has hypoglycaemia overnight and is woken up by his FreeStyle Libre 2 alarm at around 2am when his blood glucose drops below 4 mmol/L.

He speaks to his diabetes specialist nurse, Anna, who agrees they need to try and avoid night-time hypoglycaemia. She explains that Rohan is experiencing post-physical activity delayed hyperglycaemia and this is mainly because of increased insulin sensitivity following physical activity. She tells Rohan that delayed hypoglycaemia usually occurs 6–12 hours following physical activity but can happen beyond that period.

They discuss two main ways to prevent delayed hypoglycaemia from occurring:

Abbie has type 1 diabetes and takes long-acting insulin (Toujeo) before bed and short-acting insulin (Actrapid) with meals. Abbie enjoys cycling and notices that when she cycles following a meal, her blood glucose remains stable but when she cycles first thing in the morning before breakfast, she finds her blood glucose rises above her target range. She finds this frustrating and is unsure what to do about it how to prevent it from occurring. Abbie speaks with her diabetes team about why this might be happening.

Abbie has type 1 diabetes and takes long-acting insulin (Toujeo) before bed and short-acting insulin (Actrapid) with meals. Abbie enjoys cycling and notices that when she cycles following a meal, her blood glucose remains stable but when she cycles first thing in the morning before breakfast, she finds her blood glucose rises above her target range. She finds this frustrating and is unsure what to do about it how to prevent it from occurring. Abbie speaks with her diabetes team about why this might be happening.

Abbie’s diabetes team mentioned that this variability may be explained by how much insulin Abbie has on board at different times of the day. In the morning, Abbie only has her long-acting insulin on board whereas after a meal she has her long-acting insulin and her short-acting insulin on board. Insulin is needed to move glucose from the blood into the muscles so not having enough insulin on board will cause blood glucose to rise during many different types of exercise.

Abbie’s diabetes team discuss different options that might help including taking an additional short-acting insulin injection with a snack before cycling in the morning with close blood glucose monitoring afterward. They highlight how different strategies can work for different people and recommend making small changes with close monitoring to find out what works best for Abbie.

Please note: the examples above illustrate common problems people face managing type 1 diabetes and physical activity. Everyone is different and for advice about managing your individual situation we recommend speaking with your diabetes care team.

- Consider the risk of hypoglycaemia

When we exercise, the body consumes glucose as fuel. Hypoglycaemia (low glucose) is the most common complication for people with type 1 diabetes exercising. Hypos can occur, during exercise, immediately after or even several hours after, depending on the intensity and duration of the exercise.

If you think you are at risk of hypos, you need to either eat extra carbs or reduce certain insulin doses. Have a look at your exercise and insulin personal plan, and click on the following images to help you work out what to do:

Frequent blood glucose monitoring allows you to work out when, and by how much, you need to make changes to your insulin doses. The longer and more intense the exercise, the more glucose that will be consumed and so the greater the risk of hypoglycaemia.

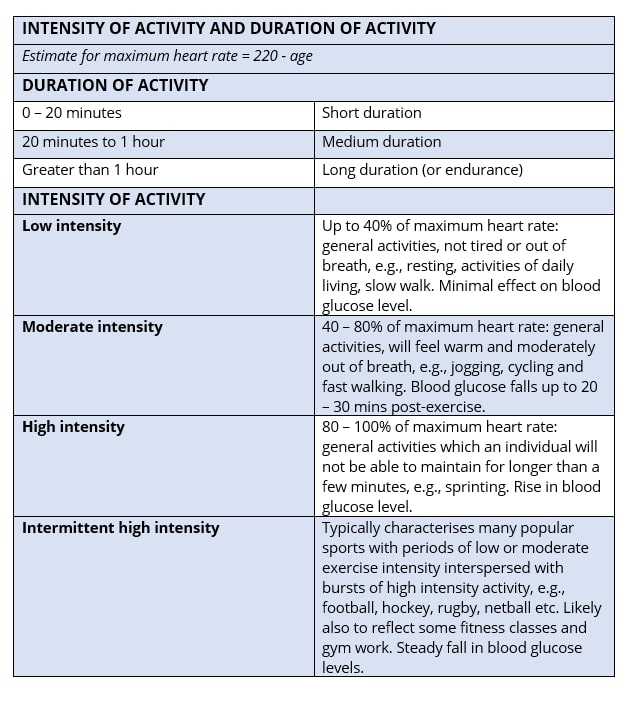

See below for a table which will help you to categorise exercise into short, medium and long duration and low medium and high intensity. Also note, that whilst most exercise will cause a glucose drop, high-intensity exercise like fast sprinting can cause a short term rise in glucose due to the release of stress hormones.

If you like alternating your activity and intensity levels at the gym, ending on a high-intensity activity can help reduce the risk of a post-workout hypo. Starting out with a high-intensity activity can also work as it will raise blood glucose levels initially, and reducing the intensity will bring the blood glucose levels back down.

It’s important to note that if the sport involves some emotional excitement or anxiety, such as a football match or competition, this will cause your blood glucose levels to rise. This can make them difficult to manage so be careful not to take a large correction dose as your blood glucose levels will normally level out when you relax again.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.